Manufacturing Polarisation in Contemporary India: The Case of Identity Politics in Post-Left Bengal

This article explores ethnographically the manufacturing of religious polarisation and violence in West Bengal, India. Since 2014, India has experienced a rise in religion-based identity conflict. Although West Bengal experienced riots during the partition of India, it remained unaffected during the subsequent three decades of Left rule. More recently, however, secular democratic forces have been marginalised and riot-like conflicts have emerged. We argue that identity consolidation in West Bengal is part of an increasing trend of religious polarisation in the country.

Article details:

2019, “Manufacturing Polarisation in Contemporary India: The Case of Identity Politics in Post Left Bengal”, International Journal of Conflict and Violence, Volume 13, pp/ 1-09 ISSN: 1864-1385

Download PDF

Original Journal url: https://www.ijcv.org/index.php/ijcv/article/view/3119

Authors:

Suman Nath

Assistant Professor in Anthropology

Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Govt. College

Rajarhat, New Town, Kolkata - 700156

sumananthro1@gmail.com

Subhoprotim Roy Chowdhury

Researcher

An Assemblage of Movement Research &Appraisal (AAMRA)

Kolkata

Introduction – Constructivism and West Bengal

Across the world, religious violence has been on the rise for decades (Juergensmeyer 2000, 2010). This includes India, where religious conflict is not uncommon, and Hindu-Muslim conflict has the capacity to split the country in two (Chhibber and Petrocik, 1989; Varshney 1998; Guha 2016). Since the formation of the pro-Hindu BJP-led government in 2014, there has been an unprecedented proliferation of Hindutva, which has included riots and lynching (“Lynch Mob Rashtra”, Frontline, 1 July 2017). The results are significant, as Guha (2016, 39) explains: “Perhaps for the first time in our history as an independent nation, serious, well respected writers are murdered, physically eliminated for their views.”

These events are particularly alarming as practices of secularism have been diluted (Nandy 1998; Bhargava 2010). Although there have been attempts to separate state affairs from religion in India, in practice, secularism is largely alien to the country (Madan 1987, 2006, 2009; Nandy 1998). Thapar (2010) finds Indian secularism to be too Brahmanical to bring communal harmony. As a consequence, India oscillates between the Indian National Congress’s accommodative secularism and a form of Hindu nationalism, most conspicuously promoted by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (Copley 1993; Ganguly 2003; Gupta 1996). Distorted histories, invented traditions, a particular form of “pseudo-nationalism”, and of late, “post-truth” hoaxes are used to stoke communal tensions (Thapar 2014; Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983; Thapar, Noorani and Menon 2016). Benei (2008) describes some of the mechanisms which increase tension between identity groups. These include the use of symbols such as the “mother country”, the national flag, and sports including mock warfare, all of which are prominent manifestations of the effort to promote Hindu nationalism in Kolhapur, Maharashtra.

Compared to the rest of the country, the consolidation of identity groups in West Bengal is more recent. It manifests itself through the intentional construction of cleavage, which is both historically informed (Laitin and Posner 2001; Thapar 2014), and has electoral intentions (Brass 2005; Pai 2013; Wilkinson 2004). The rise in the ‘construction’ of social categories, with pre-existing ethnic boundaries, has resulted in the consolidation of identity categories and increasing tension between groups (Fearon and Laitin 2000). The construction of communal tension is informed by broader structural features of civil society and government, making it important to better understand the mechanisms which shape the potential for communal violence (Fearon and Laitin 2000; Brass 1991, 2005; Anand 2005).

Constructivists explore the mechanisms of stereotyping and its relationship to identity construction and marginalisation (Banerjee 2008), and communal violence (Robinson 2005; Gupta 2011; Gayer and Jaffrelot 2012). However, ethnographic studies of identity consolidation and the mechanisms which inform how and why riots emerge are limited (Chatterjee 2017). Berti, Jaoul and Kanungo’s (2011) edited volume addresses a) the propagation of Hindutva through cultural and artistic expressions; b) the appeal of charismatic personalities affiliated with Hinduism; and c) some forms of resistance to such propagation. Scholars like Eckert (2009) and Roy (2017) draw on ethnographic principles in their studies on polarisation. However, the dynamics of manufactured polarisation in a state like West Bengal, which has not experienced this kind of conflict for decades, have received much less attention. Furthermore, there is a gap between studies on theoretical issues focused on secularism and the effects of religious polarisation and violence. While there are broader frameworks that seek to explain the symbolic-cultural and institutional mechanisms of polarisation, its everyday practices demand more attention (Benei 2008, Berti, Jaoul and Kanungo 2011).

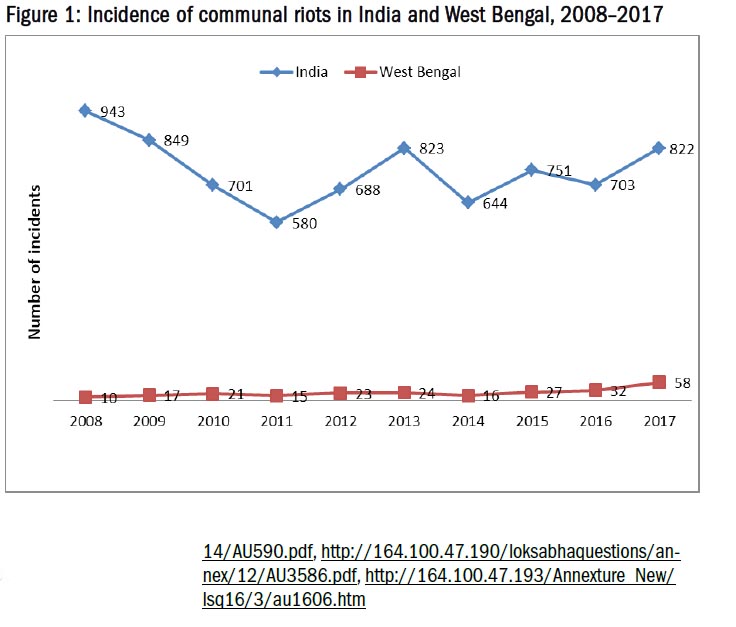

This paper seeks to address the lack of ethnographically informed studies on religious polarisation and its interface with politics in West Bengal, one of the twenty-nine states of India. Because West Bengal has recently begun to experience a rise in identity polarisation and violence (see Figure 1), it has the potential to provide important insights into the mechanisms by which fundamentalist forces rise and displace secular and democratic forces. Taking a constructivist approach based in ethnographic research, we unearth three dimensions that inform the recent increase in religious conflict in West Bengal: a) mechanisms, b) organisational base and c) everyday practices of identity consolidation. The paper illustrates these dynamics by setting out details of two such conflicts, to help develop a broader understanding of the mechanisms and everydayness of religious polarisation.

Recent Polarisations in West Bengal and the Present Study

West Bengal has experienced a rise in the number of communal riots in recent years (see Figure 1). Following an average of eighteen incidents per year in the period 2008–2014, subsequent years have seen a rise in the number of riots, meriting special attention to understanding the dynamics that have shaped this violence. In the following we therefore explore the constructions of polarisation through ethnography during the period 2014–2017.

Communalisation was a prominent phenomenon in West Bengal in the 1930s, and during the period of partition and independence. Subsequently, three decades of Naxalite and Left Front rule reduced the prominence of identity issues in the state’s political discourse (Bose 1986; Pal 2017; Das 1991, 2005; Roy 2017; Bhattacharyya 2009, 2016). However, through the second term of the Trinamool Congress (TMC) in the state in 2016, and BJP’s rule in the centre since 2014, West Bengal has witnessed a rapid change in the public and political spheres. Armed Ram Navami rallies in 2017 and 2018 and a series of riots represent prominent manifestations of these changes (“Ram Navami Rally: One Killed, Five Injured in West Bengal as Bajrang Dal Members Clash With Police”, The Wire, 26 March 2018).

With a Muslim population of 27 percent, West Bengal has a substantial presence of Muslim minorities (Census of India 2011), and consequently a history of co-habitation (including the development of several syncretic traditions) as well as occasional conflicts between the two communities. However, during the three decades it was in power, Left Front put religious and identity politics on the back foot by installing what Chatterjee (2004) termed a Political Society and Bhattacharyya (2009) described as a Party Society. Bhattacharyya (2009) argued that unlike other states in India, political parties in West Bengal transcend identity-based mobilisations. He notes several unique characteristics of Left Front politics in West Bengal, one of which is “lack of political focus on caste, religion or ethnicity-based social divisions” (Bhattacharyya 2016, 126).

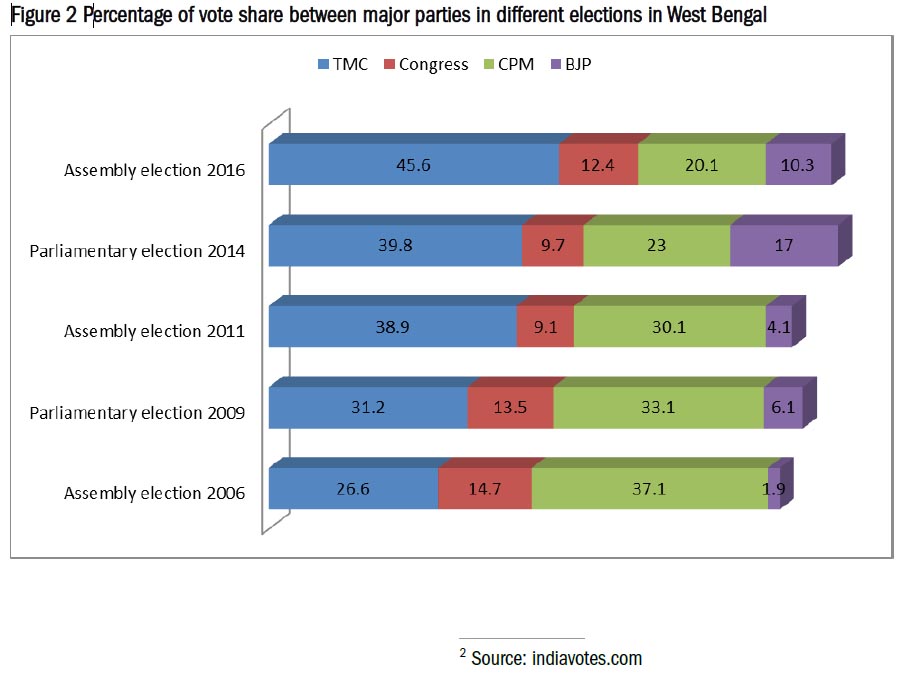

Through ethnographic study, Nath (2016 and 2018), argues that TMC has politicised “cultural” expressions through a process of “cultural misrecognition” diverting popular attention away from issues of public service delivery. An increase in budgetary allocation for the Ministry of Information and Cultural Affairs from rupees 61 crores in 2010–2011 to rupees 300 crores in 2016–2017 is one indicator suggesting a politicisation of the cultural apparatus. Keeping in mind the substantial Muslim population, the TMC-led state government devised populist policies such as provision of a monthly allowance to imams [MD1] and muezzins. The interpretation of these measures as “Muslim appeasement” partly explains the rise of the BJP and the Hindutva forces, as manifested in recent election results (see Figure 2) and Ram Navami rallies (Roy 2017). Meanwhile there have been instances of forced religious conversions, and riots that have gone unrecorded (AAMRA 2015, 2016).

It is in this context that we explore the dynamics of religious conflicts to understand the mechanisms by which polarisation is manufactured, as this represents a new dimension to the state’s politics. The study is based on ethnographic research in two places where riot-like conflict took place: Naihati-Hajinagarin in North 24 Parganas district and Rejinagar in Murshidabad district. Our aim was to uncover the inner mechanisms associated with growing polarisation and violence. To do so, we made repeated visits over a number of weeks in different phases in 2016 and 2017. As well as several week-long stays, we also made weekend visits and kept regular contact over mobile phone to track phenomena relevant to the manufacturing of polarisation. Furthermore, one of the authors resides both in Naihati-Hajinagar and in Murshidabad, which makes this study, to a significant extent, participatory in nature.

However, the study is not a classic example of participant observation; rather the work is rooted in an ethnographic sensibility that goes beyond face-to-face contact (Schatz 2009). Through ethnography, we unearth the ways in which religious polarisation is manufactured by mainstream politics – as a political strategy hitherto unused in West Bengal. We have adopted a case-based approach, elucidating the qualitative dimensions of the core issues of religious polarisation through interviews, group discussions, and tracking of important events as they unfolded. In the following section, we present two cases of polarisation in brief and then describe the core mechanisms associated with the construction of polarisation in West Bengal, which reflects a wider trend across the country.

- Hindu-Muslim Riot-like Conflict: Naihati-Hajinagar, North 24 Parganas

The Naihati-Hajinagar conflict began in 2016. It was followed by a significant number of smaller incidents of violence, and one large conflict in the district of North 24 Parganas. Naihati-Hajinagar represents a good example of how communal sentiments are constructed in a multi-ethnic population. The place falls within the TMC-held Assembly constituencies of Naihati and Bijpur. Hukum Chand Jute Mill, the largest of its kind in the world, brought people to the area from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Nepal and Orissa. This is one of the reasons why a local teacher says that the place is a “mini India”. In a group discussion in March 2017, the same interviewee argued:

… there has always been innate fissure between Hindus and Muslims at Hajinagar. However, since 2011 it has become more conspicuous and aggressive. … Not even the Left-inclined trade union leaders are able to make people think beyond their religious identities – neither during the Left regime nor at present. In fact, they also promote religious hatred at times, I have seen it!

Although Hajinagar is traditionally a Muslim dominated area, there are also isolated Hindu-Majority pocket where pan-Indian organisations like Viswa Hindu Parishad, Bajrang Dal and Durga Bahini organise their Hindutva campaigns. Evidence of these groups’ activities is seen in the proliferation of pro-Hindu slogans in local festivals. Another group discussion with both Hindu and Muslim participants revealed how religious sentiments have been fuelled since 2013, when Bajarang Dal organised a large-scale Ram Navami procession. Local people took us to some of the places on the banks of the River Hooghly (a tributary of the Ganges) where Bajarang Dal organises sword-fighting practice. Local leaders of Bajrang Dal believe that these practices are needed to protect Hindus from a possible Muslim attack. However, the performance of regular sword fights by saffron-clad people on the riverbank appears to be little more than an open display of arms and muscle to intimidate local Muslims. Attempts have also been made to initiate “Ganga Aarati” here (the spectacular worship of the River Ganges popular in Varanasi and Haridwar in North India). Such activities in recent years successfully created mutual mistrust and widened the rifts between the two communities.

Recent riots are an outcome of these everyday practices of hatred. Conflict started to surface with the violation of an age-old local agreement between Hindus and Muslims regarding conduct around the famous Chasma Baba’r Mazar. The Mazar is one of the important sacred places in the region, and was until recently a symbol of syncretism. Yousuf Kamal, popularly known as Chasma Baba, after whom it is named, is said to have possessed supernatural powers. Being a Pir, his Dargah is open to both Hindus and Muslims. In fact, the famous architecture of the Mazar was built by a Hindu businessman of Gujarat. Each year during Urs festival, local people organise Qawwali songs. Under the unwritten traditional agreement between the two communities, the only Hindu processions related to life cycle rituals would use the road adjacent to the Dargah, and no Muslims were allowed to sacrifice cows or sell beef near the Dargah. The agreement was broken in June 2016, when the local Gayatri family allegedly took the Gayatri Puja procession through this area. In response, Muslims gathered in large numbers, after which the police were called and a curfew was declared.

In response to the Gayatri procession and Ram Navami processions, Muharram rallies also turned aggressive.

While Hindus started chanting “Jai Shri Ram” [Victory to Lord Rama] at every rally including the Ram Navami and Durgostav, Muslims also started organising more conspicuous and armed rallies to celebrate Nabi and Muharram. … Now political leaders are always present in both the rallies, which they never were before TMC assumed power. We have never seen Bengali Hindus shouting “Jai Shri Ram”, nor do we remember such large Muharram rallies with sword fights. (70-year-old local businessmen, February 2017)

In this context of mutual apprehension, rumours made things even worse. The first instance of communal violence in the area centred around an assault by Hindus on a Muslim youth who had allegedly torn down the Indian National Flag at the Karbala crossing on August 15, 2016. We knew him – like many others – for his criminal activities and drug addiction. However, it remains unknown whether he actually touched the flag. When we reached the area, we learned that the youth had been detained by local Hindus at around 7:30 pm – when the national flag was not supposed to be flying. We could sense the tension of the situation and left the area. Later, one local resident reported that about seven or eight hundred Hindu people suddenly started targeting Muslim areas to loud “Jai Shri Ram” chants. They were aided by the inaction of the police, who did not arrive until after 10 pm. This incident indicates community preparedness to launch an attack on the basis of a relatively minor issue.

Local shopkeepers recall the critical role played at the beginning of the riot by local “goons” working for TMC and Bajarang Dal simultaneously. Backed by local political leaders, these goons have been involved in organised anti-social activities in the region for years. Party cadres clearly say that they find no conflict in simultaneously being a member of the ruling TMC and pro-Hindu, pro-BJP groups like Bajrang Dal. Later, in a group discussion in September 2016, one said they joined “to save Hindus from Muslims”.

The situation in the area deteriorated in the following months, and a large-scale communal conflagration took place at the end of Durgotsav 2016, when the West Bengal Chief Minister made it mandatory to immerse Durga idols on the day of Vijaya Dashami itself (which is last date for the rituals of the festival). This goes against popular convention, which is to retain idols for a few more days. The policy was in fact designed to avoid communal tensions associated with the overlapping timings of Muharram and idol immersion processions on the day after Vijaya Dashami. “She [the Chief Minister, Mamata Banerjee] became symbolically ‘Mumtaz Begam’ for the Hindus of this region,” as one of the Hindu shop-owners of Laxmigunj Market put it. It appears that this construction popularised to cultivate hatred against her. “Mumtaz Begam” later became a popular phrase used to present the Chief Minister as a “Muslim appeaser”. The shop owner continued: “… the way she dresses, with the hijab, creates an image of fear among the Hindus, and this sentiment was strategically used by Bajarang Dal”. In a group discussion in April 2017, one villager reported:

On Vijaya Dashami, someone from the idol immersion procession threw a stone at a Mazar near the Indian Paper Pulp Industry works. The impact was massive … the news spread to all the nearby Muslim localities in a moment. Although nothing happened on that night, the next day the Muharram rally was notably large and heavily armed. It started with a bomb blast and a few goons from the rally targeted Hindu houses and shops. Opportunists looted and destroyed several shops and small enterprises. Members of Legislative Assemblies of Naihati and Bijpur from TMC called for two peacekeeping rallies. One of them was attended by Muslims, the other by Hindus, and the situation remained tense. The only glimmer of hope in an otherwise depressing situation came when – even during the long hours of violence – local Muslims protected their neighbouring Hindu families and vice-versa.

We found that police refused to report this as a riot and only recorded complaints of conflict between two groups. Following this incident a series of small-scale acts of violence took place in various villages and towns in the district. Violence in Basirhat-Baduriain in July 2017 was the most brutal, and resulted in one death and the injury of many others. Together, these events illustrate that the construction and enactment of communal tension has been gaining momentum in the district.

Muslim-Muslim Riot-like Conflict: Rejinagar, Murshidabad

While everyday communalisation and the use of “goons” are important aspects in the Naihati-Hajinagar riot, Rejinagar exemplifies the rise of Islamic fundamentalism and attempts to construct a monolithic and ideal-type Islam in West Bengal. Here, there was an attack on Muslims who follow localised and multiple traditions of Pirs (known as the Pirpanthis) by Sharia followers (or Shariatis). To understand these dynamics, we conducted fieldwork in various villages in Rejinagar, Murshidabad, from November 2016 to June 2017. With a combined population of about 17,000, Teghori, Paschim Teghori and Nazirpur are three villages located in the south-east of Rejinagar, under the Andulberia II Gram Panchayat, Beldanga II Panchayat Samiti of the district of Murshidabad. The area is part of the Rejinagar Assembly Constituency, currently held by the TMC. In the three villages there are only about ten Hindu families, whilst the rest are Muslims. It is said that there used to be only one old masjid (mosque) in the region, but since 2010 there has been a substantial growth in the number of masjids.

Our research in Rejinagar reveals that a systematic attack on Pirpanthis was organised by Shariati Muslims. This took place in the context of a long-running effort by the masjid committee to persuade Pirpanthis to follow Shariati traditions. The first conflict between the two communities occurred in 2001, when Pirpanthis were attacked by Shariatis on the day of Urs. The Chistia tradition of the Urs festival calls for Qawwali and the use of traditional musical instruments, which the Masjid-based Shariati find objectionable (as contrary to the traditions and practices of “true Islam”). The use of music and dance was declared anti-Islamic by the local imam. Soon, thousands of Muslims gathered and destroyed the dargah; it was never rebuilt for fear of further tension.

More recently, on 29 October 2016, these villages suffered three further similar events. On that day, in a discussion about Islamic concept of achieving jannat (entitlement to heaven), one of the local Marfati-tradition Pirs argued that Nobel Prize–winners like Mother Teresa and Rabindranath Tagore would achieve jannat because they were pleasant and honest individuals. Immediately, the masjid microphones were used to declare these comments to be anti-Sharia, people gathered to protest against the statements, and Shariatis launched attacks on the three existing dargahs of the village. Around one thousand people completely destroyed one of the bamboo-structured Khanquasharif dargahs, and partially destroyed another. They attempted to destroy the third, but failed because of strong Pirpanthi protest from the western side of the village of Teghori. Two of the aged Chistia and Marfati followers were taken to a nearby masjid and beaten up. A man in charge of one of the Chistia tradition dargahs reports:

They took us to the local mosque and then beat us with leather sandals. They declared that we are no longer Muslims. Police did not take up FIR [First Information Report, which starts a police inquiry] against the people who belonged to Shariati traditions. They simply told us that we are only about five percent of the population, so we should try to adapt with them and follow their instructions.

During our fieldwork, local imams and masjid committees argued that, according to the Quran, non-Muslims are not entitled to go to heaven. The local Pirpanthi followers and those in-charge of the dargahs were asked to chant Qalma as they were declared to no longer be Muslims. It is notable that even this year (2018), during the Urs festival, people from Hindu localities, as well as the Shariatis, participated in large numbers. Such participation indicates that these communal incidents are the result of consolidated identity politics among the Muslim population which is of relatively recent origin. Administrative inaction suggests there is an ignorance of identity consolidation which has resulted in the destruction of folk and multiple traditions of Marfati and Chistia Mazars.

While trivial issues are systematically used to launch attacks on relatively open and syncretic traditions, it is notable that the Shariatis have largely failed to foment permanent social cleavage. Village-level everyday interactions bring people closer together, in ways that go beyond their religious identities. However, the Rejinagar violence does indicate: a) an organised move to consolidate Islamic identity and undermine local and syncretic variants; b) the cultivation of intolerance between different identities; and c) administrative ignorance of the need to address these issues. Each of these issues has the potential to disrupt the close-knit social relations within the villages.

5. Conclusions: Polarisation in West Bengal, the Broad Spectrum

These two cases in post-Left Bengal are informed by the wider political backdrop in India. The rise of the BJP has been associated with an increase in sectarian politics, which the party has historically found gives it an electoral dividend. The retreat of the Nehruvian secular consensus – seen especially in the Hindi heartland (Pai 2013) – also seems to be at work in West Bengal. Such retreat has given rise to growing levels of communal violence. Our analysis shows a significant increase in the number of riots in West Bengal, and an increase in the BJP’s share of the vote share in each of the recent elections in the region.

Recent riots seem to take two major forms: those spread by hoaxes shared through social media (Basirhat, North 24 Parganas, 2017), and those in the context of aggressive Ram Navami rallies (in Asansol-Ranigunj area of Paschim Bardhaman district in 2018) (“Ram Navami Rally: One Killed, Five Injured in West Bengal as Bajrang Dal Members Clash With Police”, The Wire, 26 March 2018). We have attempted to reveal the qualitative dimensions of the core issues that shape these dynamics through two ethnographic case studies. We find that three major factors interact to create communal tension in India: a) everyday fostering of religious sentiment by social media; b) politicisation of cultural expressions and identities along with a promotion of “invented traditions”; and c) administrative inaction. In the following section we present some of the essential dimensions of the two ethnographic cases.

First, there has been a deliberate attempt to consolidate identities. The conflict in Rejinagar exemplifies an attempt to construct an “ideal-Muslim” prototype and punish those who deviate from it. The Naihati-Hajinagar case, on the other hand, illustrates the attempts to consolidate Hindu and Muslim space, behaviour, and rituals. Such consolidations do not have clear economic associations, as argued by scholars like Bose (1986) and Das (1991), but are the outcome of a variety of invented traditions, the spread of rumours, and the promotion of ideal-types or prototypes of religious identities. Rooted in everyday practices, these constructs are fuelled by occasional conflicts.

There is a vicious cycle at work, in which people’s everyday cultural expressions are structured by ideal types of religious identities. These everyday cultural practices result in the consolidation of identity. Sentiments associated with consolidated identities enable the rapid assembly of individuals belonging to the same religion, which can often lead to communal violence. Communal violence further polarises identities. These dynamics are linked to the unclear definition of secularism in Indian democracy (Bhargava 2010; Thapar 2010, 2016), which engenders a distinctive kind of misinterpretation of secularism. Examples include the symbolic projection of the Chief Minister as a Muslim appeaser because she often appears wearing a hijab in public.[MD1] [MD2] TMC workers see the hijab-clad Brahmin Chief Minister as an image of secularism. A sizeable portion of the common people find this a threat to Hindu existence itself. The government order to stop the Durgotsav idol immersion further solidified this perception. The differences in perception regarding the Chief Minister’s appearance indicate that there is a complex and multi-layered understanding of identity issues and its interface with secularism in India.

Second, looking at the mechanisms of identity consolidation in both cases, a variety of social and cultural mechanisms are used. In Naihati-Hajinagar, invented traditions played an important role in consolidating identity-based politics. In Rejinagar, social exclusionary mechanisms were used to identify the “deviant” form of Islam, which subsequently led to violence. Both of these mechanisms are well planned and executed, involving the promulgation of fear and the cultivation of mistrust. Once these mechanisms have surfaced, they serve to further consolidate identity boundaries.

Third, there is clear evidence of invented traditions (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983); what we have done is to explore how these traditions are invented. We find that an organisation-based approach can be active in creating invented traditions that help fuel tensions. The promotion of little-known religious practices in Naihati-Hajinagar, and masjid-based movements in Rejinagar, indicates the organisational structures which instigate communal violence. Currently, the local and micro-dynamics of oscillating political alignments, which move between the TMC and a variety of pro-Hindu, pro-BJP organisations, indicate the changing nature of the interface between politics and religion in West Bengal. This is informed by a blurring of boundaries between people’s roles and their political affiliations. If we look at the partisan nature of West Bengal’s politics and administration, as vividly discussed by Bhattacharyya (2002), the administrative inaction in the face of riot-like conflicts indicates the politicisation of identity issues.

Fourth, the rise of identity based politics results in concerted attacks on relatively open and often syncretic religious traditions. Such traditions represent avenues for the integration of different currents, including the Hindu-Muslim dichotomy and form barriers to the construction of mutually exclusive consolidated identity constructs. While the Pirpanthis and their dargahs in Rejinagar are open to both Hindus and Muslims (and to women), Chasma Baba’r Majar in Naihati-Hajinagar represents another syncretic tradition. Both riot-like conflicts undermined and sought to destroy syncretic traditions. The attempted demolition of several dargahs in Rejinagar and the violation of age-old unwritten agreements regarding the use of space near Chasma Baba’r Majar are symptomatic of such endeavours.

Finally, the use of goons and the spreading of rumours indicate planning behind the violence and reinforce the organisational base for the conflict. These factors indicate that the everydayness of identity consolidation and occasional spur of invented tradition is part of a long-term political process. This is a new political mechanism, distinct from the dynamics at work under the state’s earlier Left regime.

These five major dimensions of increasing polarisation reflect the mechanisms that inform growing intolerance in West Bengal and across India. With more riots in 2018 associated with Ram Navami rallies – an invented tradition for West Bengal – it seems clear that West Bengal’s festivals are becoming increasingly riot-prone (as Jafrellot 2005, studied elsewhere). Further, there is a simultaneous process of promoting such new traditions and attacking existing syncretic traditions to reinforce Hindu-Muslim cleavage. We would argue that the five dimensions can be used to explain similar issues elsewhere.

West Bengal stands at a crucial historical juncture, witnessing an organised, conscious effort to polarise identity groups. The rise of identity politics in West Bengal must, therefore, be seen in contrast to the three-decade long Party Society. Issues such as polarised peacekeeping rallies, conspicuous presence of Members of Legislative Assemblies and other leaders in religious festivals, alongside administrative inaction, reflect indirect support for growing communal tensions. The alleged connection between Bajrang Dal and the local TMC, and the lack of administrative measures to stop such conflicts, are symptomatic of both BJP’s and TMC’s promotion of sectarian politics.

Importantly, the sectarian politics frequently attributed to the rise of the BJP often has localised formulations and dynamics. Dual membership of TMC cadres indicates these local dimensions. Present conflicts are therefore fabricated to consolidate religious and ethnic identities, and must be seen as conscious attempts to “invent” a purposively disturbed present to shape the future potential for conflict. As Thapar (2014) says, we use the past to legitimise our present social order. We argue that the religious conflicts in West Bengal must be seen from this perspective and should not be regarded as simple incompatibilities between two different ideologies and identities or as a simple outcome of electoral politics.

References

AAMRA. 2015. Dharmantakaran: Paschimbanga Parjay (Bengali). Kolkata: AAMRA.

AAMRA. 2016. Kaliachak Violence: A Fact-Finding Report. Kolkata and Mumbai: AAMRA and Centre for Study of Society and Secularism.

Anand, Dibyesh. 2005. The Violence of Security: Hindu Nationalism and the Politics of Representing “the Muslim” as a Danger. Round Table 94 (379): 203–15.

Nath, Suman. 2016. Political Consciousness and Decision Making: An Ethnographic Study on the Dialectics of Rural Public Sphere and Local Governance in West Bengal. Ph.D. diss., University of Calcutta.

Nath Suman. (2018). “Cultural Misrecognition” and the Sustenance of Trinamool Congress in West Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly 53 (28): 92–99

Banerjee, Mukulika, ed. 2008. Muslim Portraits: Everyday Lives in India. New Delhi: Yoda.

Benei, Veronique. 2008. Schooling Passions: Nation, History, and Language in Contemporary Western India. Stanford: Stanford University Press

Berti, Daniela, Nicolas Jaoul, and Pralay Kanungo, eds. 2011. Cultural Entrenchment of Hindutva: Local Mediations and Forms of Convergence. New Delhi: Routledge.

Bhargava, Rajeev. 2010. The Distinctiveness of Indian Secularism. In Indian Political Thought: A Reader, ed. Aakash Singh and SilikaMohapatra, 99–119.London: Routledge.

Bhattacharyya, Dwaipayan. 2009. Of Control and Factions: The Changing “Party-Society” in Rural West Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly 44 (9): 59–69.

Bhattacharyya, Dwaipayan. 2016. Government as Practice: Democratic Left in a Transforming India. Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Bhattacharyya, Harihar. 2002. Making Local Democracy Work in India: Social Capital, Politics and Governance in West Bengal. New Delhi: Vedam.

Bose, Sugata. 1986. Agrarian Bengal: Economy, Social Structure and Politics: 1919–1947. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Brass, Paul R. 1991. Ethnicity and Nationalism: Theory and Comparison. New Delhi: Sage

Brass, Paul R. 2005.The Production of Hindu-Muslim Violence in Contemporary India. Seattle: University of Washington Press

Census of India. 2011. Population by Religious Community: West Bengal. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-01/DDW19C-01%20MDDS.XLS, accessed 13 April 2017.

Chatterjee, Anusua. 2017. Margins of Citizenship: Muslim Experiences in Urban India. New Delhi: Routledge

Chatterjee, Partha. 2004. The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most Parts of the World. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

Chhibber, Pradeep. K., and John R Petrocik. 1989. The Puzzle of Indian Politics: Social Cleavages and the Indian Party System. British Journal of Political Science 19 (2):191–210

Copley, Antony. 1993. Indian Secularism Reconsidered: From Gandhi to Ayodhya. Contemporary South Asia 2 (1): 47–65

Das, Suranjan. 1991. Communal Riots in Bengal 1905–1947. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Das, Suranjan. 2005. The 1992 Calcutta Riot in Historical Continuum: A Relapse into “Communal Fury”? In Religious Politics and Communal Violence, ed. Steven I Wilkinson, 272–79. New Delhi: Oxford.

Eckert, Julia. 2009. The Social Dynamics of Communal Violence in India. International Journal of Conflict and Violence 3 (2): 172–87.

Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. 2000. Violence and the Social Construction of Ethnic Identity. International Organization 54 (4): 845–77.

Ganguly, Sumit. 2003. The Crisis of Indian Secularism. Journal of Democracy 14 (4): 11–25.

Gayar, Laurent, and Christophe Jaffrelot, eds. 2012. Muslims in Indian Cities: Trajectories of Marginalsation. London: Hurst.

Guha, Ramchandra. 2016. Democrats and Dissenters. Gurgaon: Penguin Random House.

Gupta, Dipankar. 2011. Justice Before Reconciliation. New Delhi: Routledge

Gupta, Smita. 1996. India: From Consensus to Confrontation. Contemporary South Asia 5 (1): 5–18.

Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terrence Ranger, eds. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2005. The Politics of Processions and Hindu-Muslim Riots. In Religious Politics and Communal Violence, ed. Steven I. Wilkinson, 280–307. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Juergensmeyer, Mark. 2000. Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Juergensmeyer, Mark. 2010. The Global Rise of Religious Nationalism. Australian Journal of International Affairs 64 (3) 262–73.

Laitin, David, and Daniel N. Posner. 2001. The Implications of Constructivism for Constructing Ethnic Fractionalization Indices. APSA-CP 12 (winter), 13–17.

Madan, T. N. 1987. Secularism in its Place. Journal of Asian Studies 46 (4): 747–59.

Madan, T. N. 2006. Images of the World: Essays on Religion, Secularism and Culture. New Delhi: Oxford University Press

Madan, T. N. 2009. Modern Myths, Locked Minds: Secularism and Fundamentalism in India. New York: Oxford University Press

Nandy, Ashis. 1998. The Twilight of Certitudes: Secularism, Hindu Nationalism and Other Masks of Deculturation. Postcolonial Studies: Culture, Politics, Economy 1 (3): 283–98.

Pai, Sudha, ed. 2013.Handbook of Politics in Indian States: Regions, Parties and Economic Reforms. New Delhi: Oxford

Pal, Madhumay, ed. 2017. Naxalbari: BajranirghosherAgungatha (Bengali), vols. 1 and 2. Kolkata: Dip Prakashan.

Robinson, Rowena. 2005. Tremors of Violence: Muslim Survivors of Ethnic Strife in Western India. New Delhi: Sage

Roy, Rajat. 2017. Communal Politics Gaining Ground in West Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly 52 (16): 18–20.

Schatz, Edward, ed. 2009. Political Ethnography: What Immersion Contributes to the Study of Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Thapar, Romila, A. G. Noorani and Sadanand Menon. 2016. On Nationalism. New Delhi: Aleph.

Thapar, Romila. 2010. Is Secularism Alien to Indian Civilisation? In Indian Political Thought: A Reader, ed. Akash Singh and Silika Mohapatra, 75–86. London: Routledge

Thapar, Romila. 2014. The Past as Present: Forging Contemporary Identities Through History. New Delhi: Aleph.

Varshney, Ashutosh. 1998. Why Democracy Survives. Journal of Democracy 9 (3): 36–50.

Wilkinson, Steven Ian. 2004. Votes and Violence: Electoral Competition and Ethnic Riots in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

[MD1]The words are used in the general sense so (in our style book at least) lower case (while acknowledging that there are other interpretations)

আমরা: এক সচেতন প্রয়াস

AAMRA is an amalgamation of multidisciplinary team of researchers and activists erstwhile worked as an assemblage of movement, research and activism. Popular abbreviation of AAMRA is, An Assemblage of Movement Research and Appraisal.-

‘We are same boat-brother’, Picnic of Bengal Peace Centre, Bhatpara, 26 December, 2021

Our aim is not to only talk about peace but to involve... -

Rally to celebrate World Environment Day, Kolkata, 5 June, 2022

‘Environment Rights Movement’, a platform of different... -

ধর্মান্তরকরণ : পশ্চিমবঙ্গ পর্যায়

ভারতে রাজনৈতিক হিন্দুধর্মের... -

Seminar on Role of the Mediation in Conflict Resolution, IDSK Hall, Kolkata, 22 November, 2022

This seminar explores how a conflict area complicates...