Communalising the Migrants in the middle of Covid-19 crisis in India

Covid-19 in India is not just a virus which has disrupted people’s everyday life. It is not just a fight with the crippling healthcare system or the economic disruption in which millions are going to suffer; it is also the social constructs associated with the disease.

Article details:

2020, Communalising the Migrants in the middle of Covid-19 crisis in India, The Frontier Weekly, May 16, 2020

Journal url: https://www.frontierweekly.com/views/may-20/16-5-20-Communalising%20the%20Migrants.html

Download PDF

Author:

Suman Nath

Department of Anthropology

Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Government College

New Town, Kolkara

Covid-19 in India is not just a virus which has disrupted people’s everyday life. It is not just a fight with the crippling healthcare system or the economic disruption in which millions are going to suffer; it is also the social constructs associated with the disease. India is a country where people have a tendency to see things hierarchically; perhaps an extension of the caste system which gets manifested in a variety of ways which makes Indians as Louis Dumont (1980) said Homo Hierarchicus. We have this deeply ingrained tendency of seeing things in terms of us/them dichotomy. While the caste hierarchy including the century old constructs of untouchability is still in practice in different places of the country, Covid-19 brings home new challenges. The precautionary measures because of its highly contagious nature include ‘untouchability’ to be practiced at individual level, it has begun to be a new normal to avoid people and remain untouched. However, the trouble just starts here for a country which has over the years weakened the idea of secularism.[1] India has for long been oscillating between Congress’s accommodative secularism and a particular form of Hindu nationalism which has established its firm grip over a substantive part of the country’s public sphere since 2014 when the Bharatiya Janata Party has came to the power. The country has seen manufacturing of prominent cleavage based on identity politics first through mob-lynching of Muslims (Salam 2019), through riots of low intensity (Nath and Roy Chowdhury 2019a, b), finally in the amendment of Citizenship Act which for the first time used religion as one of the criterion to grant citizenship (Washington Post 2019). Such a move has prepared the ground for an extreme form of polarization as for Varshney (1998), Hindu-Muslim conflict carries the capacity to split the country.

Covid-19 came to India in this back drop and has been since then used to promote polarisation even further. Tablighi Jamaat event – one of the super spreaders of Covid-19 marked off the beginning of identifying Muslims with Corona. A grand narrative has been manufactured which equated Muslims with Covid-19 spreader. All the popular social media platforms have been flooded with misleading information and photos. They include inter alia posting some old photograph of a busy market and then claiming them to be the photos during lockdown in places like Metiaburuz, Rajabazar or Park Circus – all prominent places of Muslim settlements in Kolkata. Even in the official letter exchange episode in West Bengal there were mentions of “minority appeasement” that has been condemned by Imams[2]. The latest to this episode of Corona-Communalism connect is the communalisation of migrant labourers who have slowly began to get some relief from the government as special trains are bringing them back home. As the news started to reach at different localities that trains full of migrant labourers are going to be arrived soon, the question of who are they, what are they, how damaging this might get became a new discourse. In a polarized public sphere the obvious turn is that the nature of discourse will take a communal turn. So, when the news of migrant labourers’ arrival has reached to a place called Krishnanagar, in Nadia district, locals reported to get messages filled with ‘they will be coming’, ‘you know those who stay at karimpur,’ ‘they are going to return.’ The relatively easy question is who are they? Yes they are the Muslims. A much more difficult question is why are they? I will try to make some sense of the both in the following.

Although, the nature of polarisation with so many years of mutual avoidance (also coexistence at places) might appear natural, it requires a little curiosity to know why these are not natural. First of all, if we look at the district Nadia we will see that according to 2011 census it has a Muslim population of 26.73%, while in Karimpur block it is 43.24% and in Tehatta block it is 36.13%. Districts like Murshidabad which has one of the highest out migration rates in West Bengal has about 66% Muslim population. Hence, the question about their identity has a simple statistical logic that remains intentionally ignored in the posts shared with communal intentions. Hence, as people from these places migrate there will be a substantive number of Muslims. Now the difficult question is to know why do they migrate?

In order to understand the reasons for their migration we need to look at the agricultural performance of the country at large. In a state which still has a good performance in farming, it can be comfortably guessed that rural migrants do have an agricultural root. The land reform movement although has allocated land to a substantive number of landless people, over the generations the effect of reform has become minimized and there has been an increase in the number of wage earners. What about the agricultural performance in terms of employment generation? If we go through some of the contemporary literature we will find that the farming related employment generation since 1990 has shown a steady decline. During the same time there has been a substantive downfall of loan seeking farmers (Gupta 2005; Binswanger-Mkhinze 2003, Timmer 2009, World Bank 2010, Shetty 2006,2011). Furthermore, there has been a stiff competition and party interference in employment seeking people from the agriculture (Nath and Chakrabarti 2011, Nath, 2020). This is also the time when there is a slow but steady rise in the technocratisation of farming which started to reduce the requirement of labourers. In 2019 November I stayed in Gushkara, Purba Bardhaman, one of the relatively well-off agriculture based locale of the state for a couple of weeks. My aim was to study the nature of farming politics. I was amazed to know that in order to save money local farmers form informal coalition and bring harvesters from Haryana along with a driver. Earlier able bodied Muslim migrants used to come and stay throughout the period of harvesting and provided the much needed labour input. Even today many of the rich farmers have arrangements for their stay. With technology input such work has been reduced drastically over the years. While Gushkara is one example, rising work insecurity has been a challenge for a decade now which was one of the reasons for which the Government of India has launched the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme in 2006. Although it has ensured a 100 day of work per family, it nevertheless could not stop people from migrating because of rising poverty, increasing insecurity and relatively better earning opportunities in the cities nearby and at distant places.

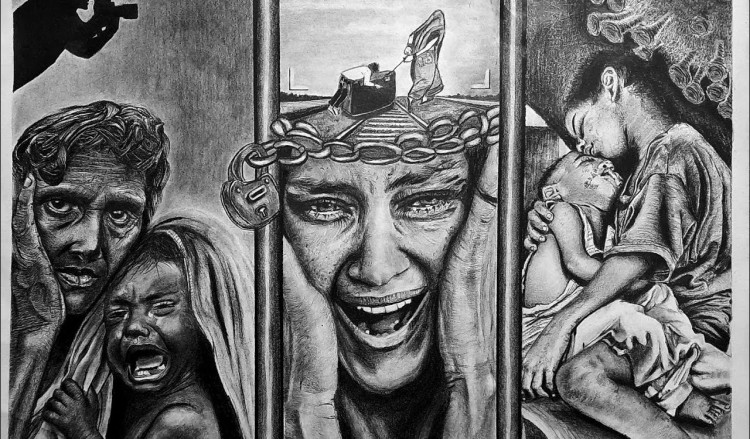

Cities of India have shown a stark contrast during this period. This is also the time when Indian economy started to grow at an average 6 to 7 percent in creating the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per year. Much of the money began to flow in the service industries. One major impact of such growth story is an increasing demand for ‘urban life’ – the real estate. The real estate made it a compulsion for the cities to expand which has seen unparallel investments in building the urban infrastructure which ranges from roads and metros to the shopping malls. All of which required able bodied, hardworking, labourers. This has resulted in the generation of labour contractors who could easily bring the surplus labourers from the agriculture-based villages. They were hard working, able bodied and had no options left than to go and stay in the darkest ditches of India’s growth story. So, in a hypothetical situation an individual might have taken the challenge of going out and staying in an alien place only to get a sanction to come back once in a while, may be in a festive season. Because of this migration his family could afford their child’s education, two meals a day and medicines for the elderly. This is more than what a poor, landless, marginal farmer’s son can actually dream of. This has an attraction and soon he finds himself accompanied by his friends, and relatives. Not only has the earning from the farming reduced, earning from the non-farm activities over the years have shown a very slow growth that cannot afford people to stay back in the villages (Binswanger-Mkhize 2013). One needs to add the dimensions of yearly disasters like cyclone Aila which has destroyed a vast chunk of farm land in South 24 Parganas, or the river erosion related problem which has made thousands homeless in Murshidabad, Nadia including the place called Karimpur. Huffington post in a 2017 article intensively covers the effect of river erosion which pushed hundreds of families to migrate from Karimpur itself. They didn’t migrate because of a better choice; they went out because they didn’t have any option left. A few cartoons which tried to portray the dynamics of migrant workers woes grabbed attention, picture 1 is one of them. It clearly shows how forgetful Indian cities are to their builders.

Clearly, the migrants walking hundreds of miles without food, physically carrying their little belongings are nobody to the state. They have faced ignorance before and they know they will be ignored again. What can we get by infusing a little bit of communal sentiment in this story? We get what Afrazul, a migrant labourer got in the hand of a saffron fanatic Sambhulal. Can we really forget what happened afterwards when Sambhulal was made a hero by the like minded mass, yes, we saw a new reality. A new normal for communal India had surfaced through the darkest nights of lynching episodes. Social media was full of such videos and photographs where Muslims were lynched, and mainstream media stopped making large headlines of lynching issues (Salam 2019).

We are still searching for religion while we are playing the age-old game of untouchability in the time of Covid-19. Can we sneak a bit into the life of the people who are building an apartment nearby? Who are they? What do they do? I am teaching in a college in the heart of the built-in city of New Town, Kolkata since 2016. I have seen the college building vertically extending itself from a two-story building to a four story one. The work continued for years round the clock and I have closely seen the people – the migrants. I have seen boys belonging roughly at the same age of our students climbing stairs with bricks on their head. Our students have on several occasions expressed the fact that they consider themselves lucky to be able to afford to study. We discussed the fact, we tried to know their compulsions and sometimes we weep silently with helplessness. They were not given a minimum security. They do not even have a minimum insurance. One day in the month of hot May a worker fell from the third floor. He was taken to a hospital to undergo a serious operation. After such a sad incident with mounting pressure trapping net was installed. I am reasonably sure his family would not have been given any compensatory money had there not been a pressure from the students union on the agency which undertook the work. This is just an example of what is going on every day in New Town Kolkata, or perhaps thousands of other places in the name of growth and development. Who are the martyrs of such progress? Should only the accident matter? Perhaps not! They have unusually long working hours, no place to sleep properly, no proper meal and no social security. However, they continue to build up the cities. Behind every air-conditioned shopping mall, IT offices with postmodern architecture, hot bitumen and eye catching boulevard there are thousands of tiring mornings, exhausting days, smelly evenings and sleepless mosquito infested hot and humid nights. Yet, there are people and organizations looking for the religion in hardened rope like unnourished muscular bodies. They are looking for the identity dynamics in sweat, blood and blisters.

We are compelled to seek identity in the migrant labourers. Mainstream and social media is playing a fantastic role to sow the seeds of hatred so that a blood lust can be enjoyed in the middle of a Covid-19 crisis. Can we really afford to have riots now? I know people will unanimously say a big no. Do we need to teach ‘them’ a lesson? I know many will silently say yes! What happens when you face a riot? Aamra Ek Sachetan Prayas (A group of researchers and activists on conflict and coexistence study) has been regularly studying the riot affected areas of West Bengal through repeated visits to places like Dhulagarh, Naihati-Hajinagar, Baduria-Basirhat, Asansol-Ranigunj, and Bhatpara-Kankinara (Conflict Area Study: 1,4,7, Aamra Ek Sachetan Prayas; Nath and Roy Chowdhury 2019a, b). Let us take a look at the case of Bhatpara. How the riot affected people are living now? The worst affected are the jute-mill settlement areas in Bhatpara-Kankinara. We all expect government to stand by us when we have no one else. We also know it requires papers, papers for entitlements like a Ration Card. What will happen if your card is lost or perhaps been turned into ashes? What if your house is half broken and you literally have nowhere to go? What if you don’t have food but you hear the sound of crude bombing still continuing somewhere in the vicinity? What if you get some staples so that you don’t starve to death but you don’t have access to soap or water? All these and much more is what is happening with the riot affected people in the region (Roy Chowdhury, Communalism in the time of Covid, Frontier, 2020). Before you forward any communally charged messages just remember the affected include people from both the communities. If your neighbour is not safe you are unsafe as well.

Why don’t you ask another difficult question, “Why it is the Muslims who migrate the most?” If you are a seeker you will end up reading the Sachar Committee Report. Do you know 25% of the Muslim children cannot afford to go to a school simply because there is no school nearby? Let us don’t go into the details of the nature of behavior they often receive from others. Do you know in a college only one among 25 others is a Muslim, and for a University it is one in 50? Among the employees in the Indian Railways Muslims constitute only 4.5% of the total workforce and among them 98.5% works in the lowest rank. Ask any contractor and he will tell you that he keeps the most physically challenging work for the Muslim men of his team. On any given day people undertaking the most labourious roofing work are the Muslims, while Hindus work for brick placing. In a 2006 paper Kumar et al. showed that 63% of the workforce undertaking building construction and 79% working in the metro projects are the Muslims. Do you think that these are mere coincidence that the work distribution is skewed both quantitatively and qualitatively? No it is not. These facts reveal two important things first, that the government has not taken adequate measure to do justice to the Sachar Committee findings, and second, the us/them dichotomy, the hierarchy, the untouchability has infected everyone from the person who creates and spread hatred occupying in a high echelon of the society to the migrant worker who is taking a nap on some highway on his/her way back to the village. This is why identity issue transcends class positions. This is why we find prominent social geography in an otherwise cramped slums of Bhatpara, this is why people participate in riot even when their stomach is empty!

Notes

1. Madan (1987, 2009) and Nandy (1998) have adequately discussed, the very notion of secularism is quite alien to the country. For Thapar (2010) secularism focuses on Brahminical segment of Hinduism and excludes others which indulges communal violence.

2.https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/apr/27/bengal-imams-urge-governor-dhankhar-to-retract-his-minority-appeasement-comment-2136059.html

References

Binswanger-Mkhinze, Hans P (2013): “The Stunted Structural Transformation of the Indian Non-Farm Sector,” Economic and Political Weekly,Vol48, No 26-27, pp 5-13.

Dumont, L. (1980). Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gupta, Dipankar (2005): “Whither Indian Village: Culture and Agriculture in ‘Rural’ India,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 40, No 8, pp. 751-758.

https://www.huffingtonpost.in/village-square/hungry-river-padma-is-forcing-people-to-migrate-in-search-of-a-livelihood_a_23317997/

Madan, T. N. (1987). Secularism in its Place. The Journal of Asian Studies 46(4): 747-759.

Madan, T. N. (2009). Modern Myths, Locked Minds: Secularism and Fundamentalism in India. New York: Oxford University Press

Nandy, A. (1998). The Twilight of Certitudes: Secularism, Hindu Nationalism and Other Masks of Deculturation. Postcolonial Studies: Culture, Politics, Economy 1(3): 283-298.

Conflict Area Study: 1,4,7, Aamra Ek Sachetan Prayas (An Assemblage of Movement Research and Appraisal), Kolkata.

Nath S, Roy Chowdhury S (2019a). Manufacturing polarisation in contemporary India: The case of identity politics in post-left Bengal. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 13, 1-19

Nath S, Roy Chowdhury S (2019b). Mapping polarization: Four ethnographic cases from West Benga. Journal of Indian Anthropological Society, 54, 51-64

Nath, S and Chakrabarti, B. (2011): “Political Economy of Cold Storages in West Bengal,” Commodity Vision, Vol 4, No 4, 36-42.

Nath, S. (2020). People-Party-Policy Interplay in India: The Micro-dynamics of Everyday Politics in West Bengal, c. 2008 – 2016. New York: Routledge

Roy Chowdhury, S. (2020). Communalism in the time of Covid-19. The Frontier Weekly. https://www.frontierweekly.com/views/may-20/1-5-20-Communalism%20in%20the%20time%20of%20Covid-19.html

Salam, Z. U. (2019). Lynch Files: The Forgotten Saga of Victims of Hate Crime. New Delhi: Sage

Shetty, S. L. (2006): “Policy Responses to the Failure of Formal Banking Institutions to Expand Credit Delivery for Agriculture and Non-Farm Informal Sectors: The Ground Reality and Tasks Ahead,” Paper presented at ICRIER’s monthly seminar on India’s Financial Sector, New Delhi: ICRIER, 14th November.

Shetty, S. L. (2011): Agricultural Credit and Indebtedness: Ground Realities and Policy Perspectives, In D. Narasimha Reddy and Srijit Mishra, eds, Agrarian Crisis in India, pp 61-86. New Delhi: Oxford

Sukla, Kumar, K., Tripathi, Sushama, Mishra and Sanjay, “Out Migration from Rural Villages In Eastern Uttar Pradesh; A Micro- Level Study" Demography, India, Vol 35, No- 2(2006), pp. 337- 351.

Thapar, R. (2010). Is Secularism Alien to Indian Civilisation? In Indian Political Thought: A Reader, ed.Akash Singh and Silika Mohapatra, 75 – 86. London: Routledge

Timmer, Peter, C (2009): A World Without Agriculture: The Structural Transformation in Historical Perspective. Washington DC: American Enterprise Institute.

Varshney, A. (1998). Why Democracy Survives. Journal of Democracy 9(3):36-50.

Washington Post (2019) India Passes Controversial Citizenship Law Excluding Muslim Migrants, December11, accessed from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/india-poised-to-pass-controversial-citizenship-law-excluding-muslim-migrants/2019/12/11/ebda6a7e-1b71-11ea-977a-15a6710ed6da_story.html on 4.4.2020

World Bank (2010): Perspective on Poverty in India: Stylized Facts from Survey Data. Washington DC: World Bank.

আমরা: এক সচেতন প্রয়াস

AAMRA is an amalgamation of multidisciplinary team of researchers and activists erstwhile worked as an assemblage of movement, research and activism. Popular abbreviation of AAMRA is, An Assemblage of Movement Research and Appraisal.-

Seminar on Communalism, Fundamentalism and its expanded territory-Jihad, Conversion and Intolerance, Kolkata,16 May, 2016

On 16 May, 2016 we had organised a seminar on ‘Communalism,... -

Lord Ram: Where was he born? by Ram Puniyani

Ram Puniyani explores the controversies which are overlooked... -

Rejinagar Shariyati Violence

In contemporary Bengal, one of the most important trends... -

West Bengal: Shariyati Violence against Sufi centers

Contemporary Bengal has seen several strategic attempts...